One of the first things I learned when coming to Longyearbyen, is that it is a very sought after place by creatives. The Arctic is a destination where many people come to re-discover or realise themselves, and I am not necessarily excluding myself from this category. As a result, the community here is continually being approached by artists, researchers and journalists with project proposals which, although interesting, often require the extraction of knowledge, time and resources from the locals. While this is generally welcomed, it is also important that we as visiting creatives do not only seek to benefit from the community’s goodwill, but that we also give something back and contribute positively to making Longyearbyen a vibrant town to live.

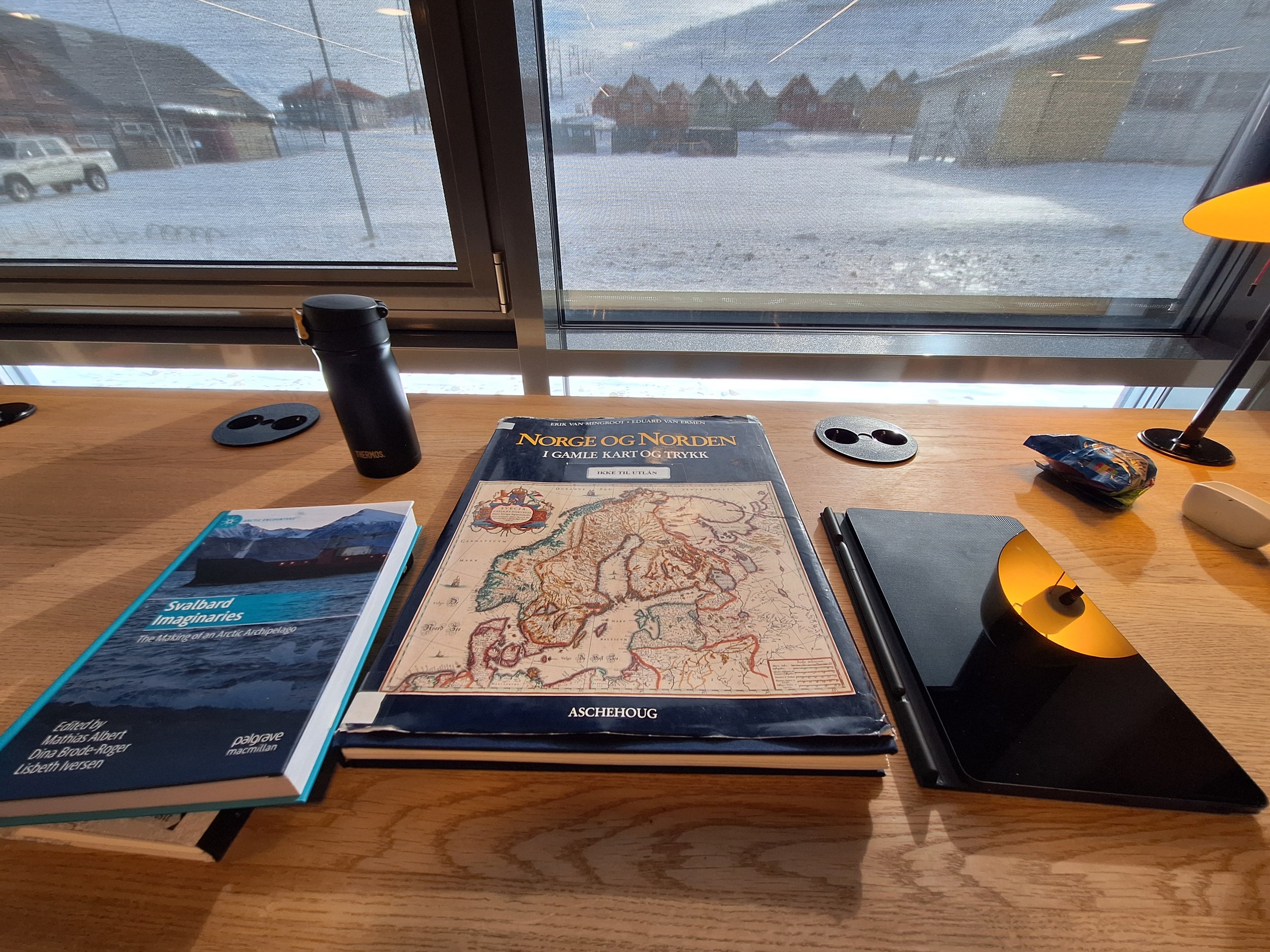

As part of our residency with ARTICA, we are obliged to share our research and/or practice with the local community in the form of talks, workshops, performances, lectures, exhibitions etc. One really nice thing that Charlotte, the Director of ARTICA said, was that the best thing a resident artist can leave behind is not necessarily a finished artwork, but an experience. Nothing is more valuable than exchanging skills and knowledge. As a result, ARTICA hosts a range of diverse workshops and events, most recently a mooncake workshop with visiting pastry chef Ethan Kan, as well as a sun medallion workshop for kids in order to welcome the return of the sun after a long, dark arctic winter.

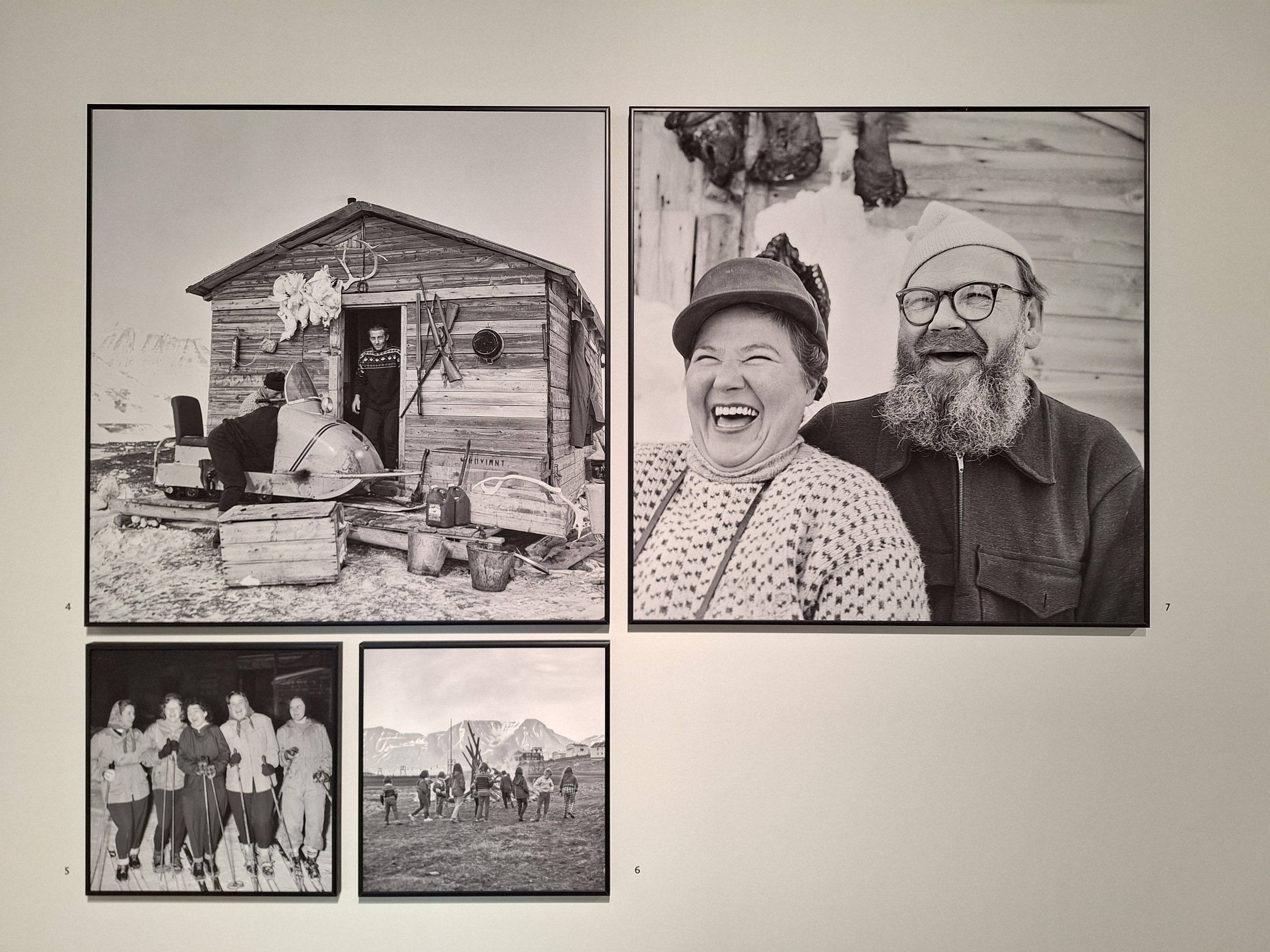

Photo: ARTICA

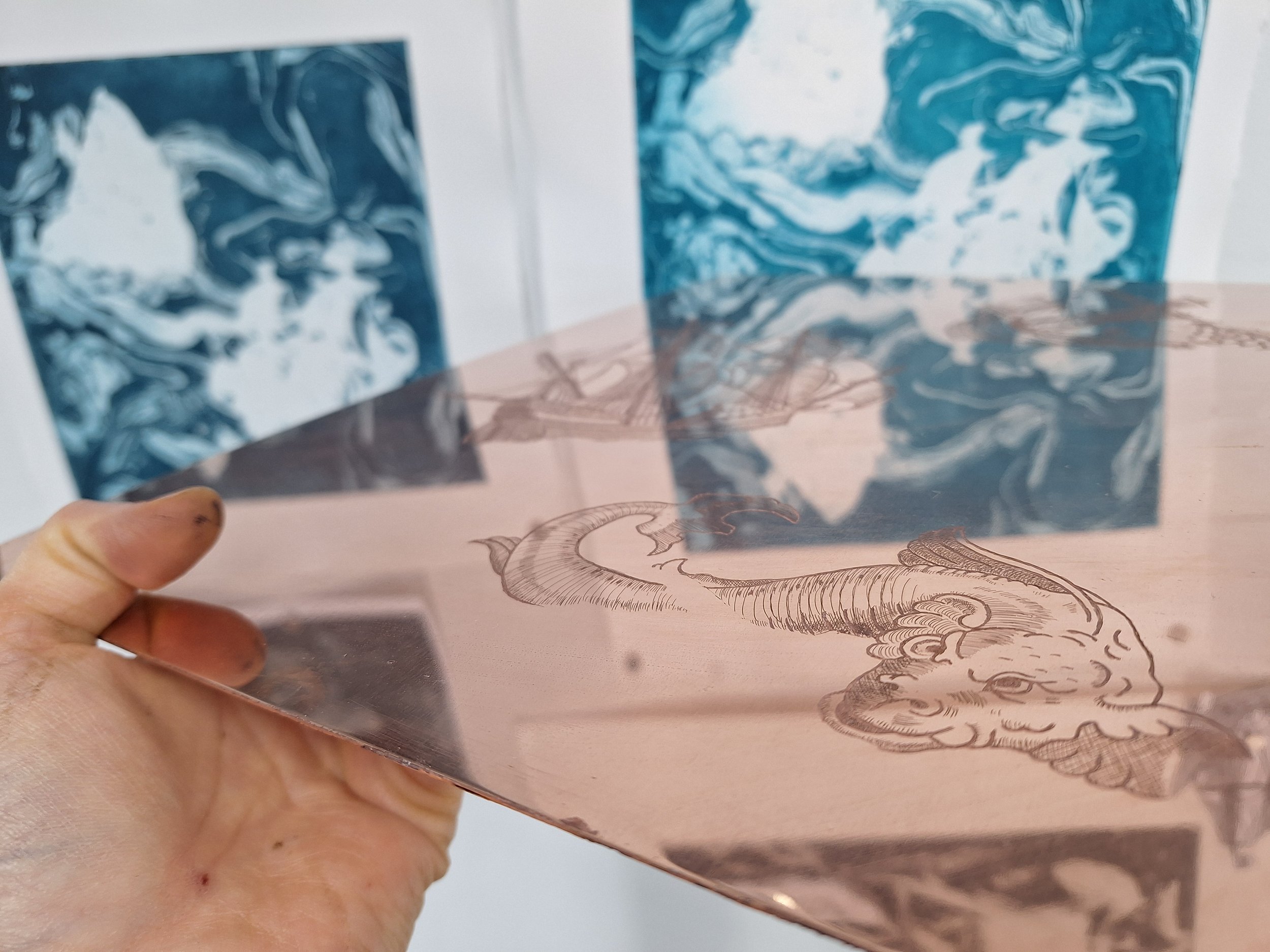

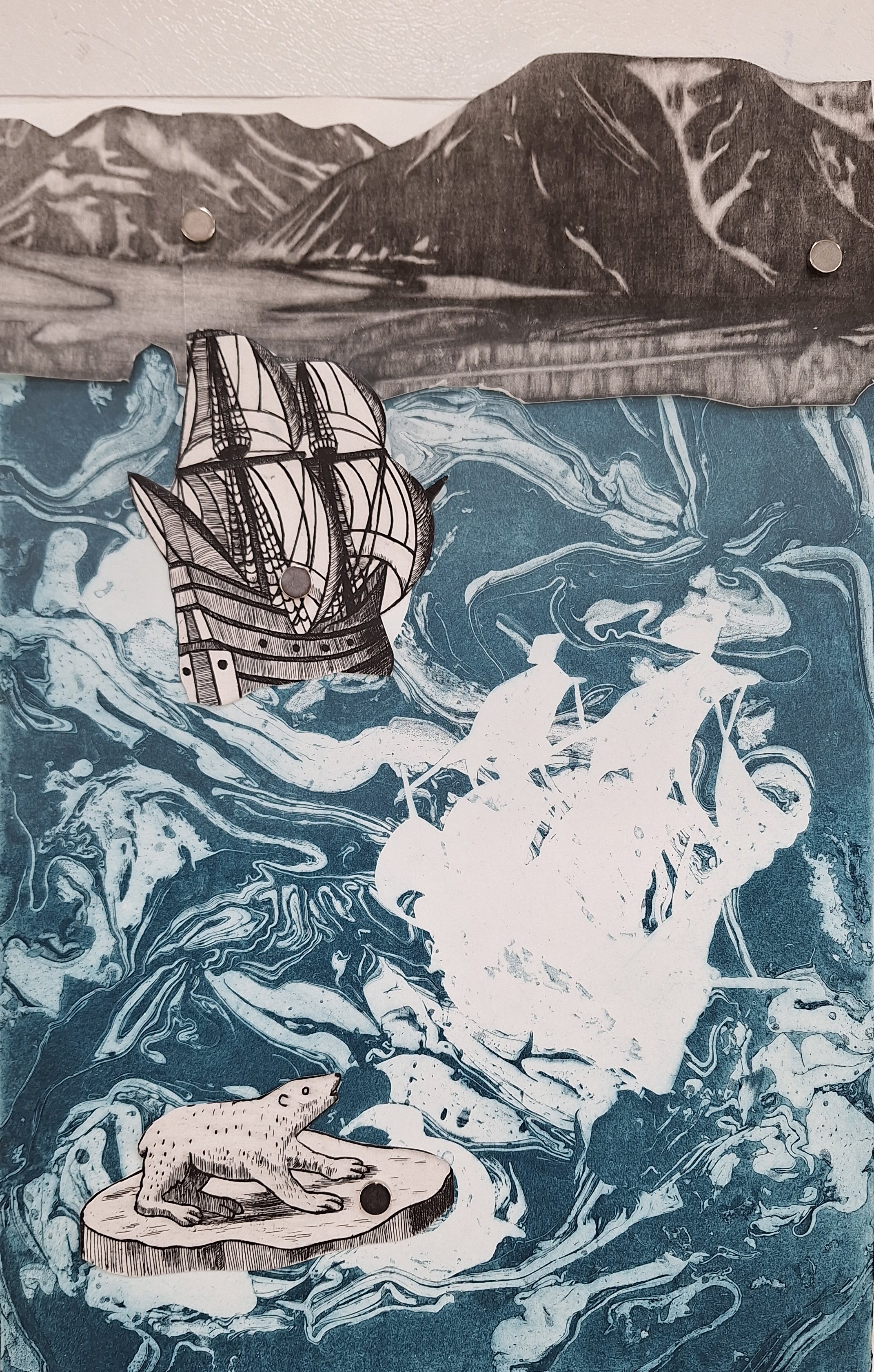

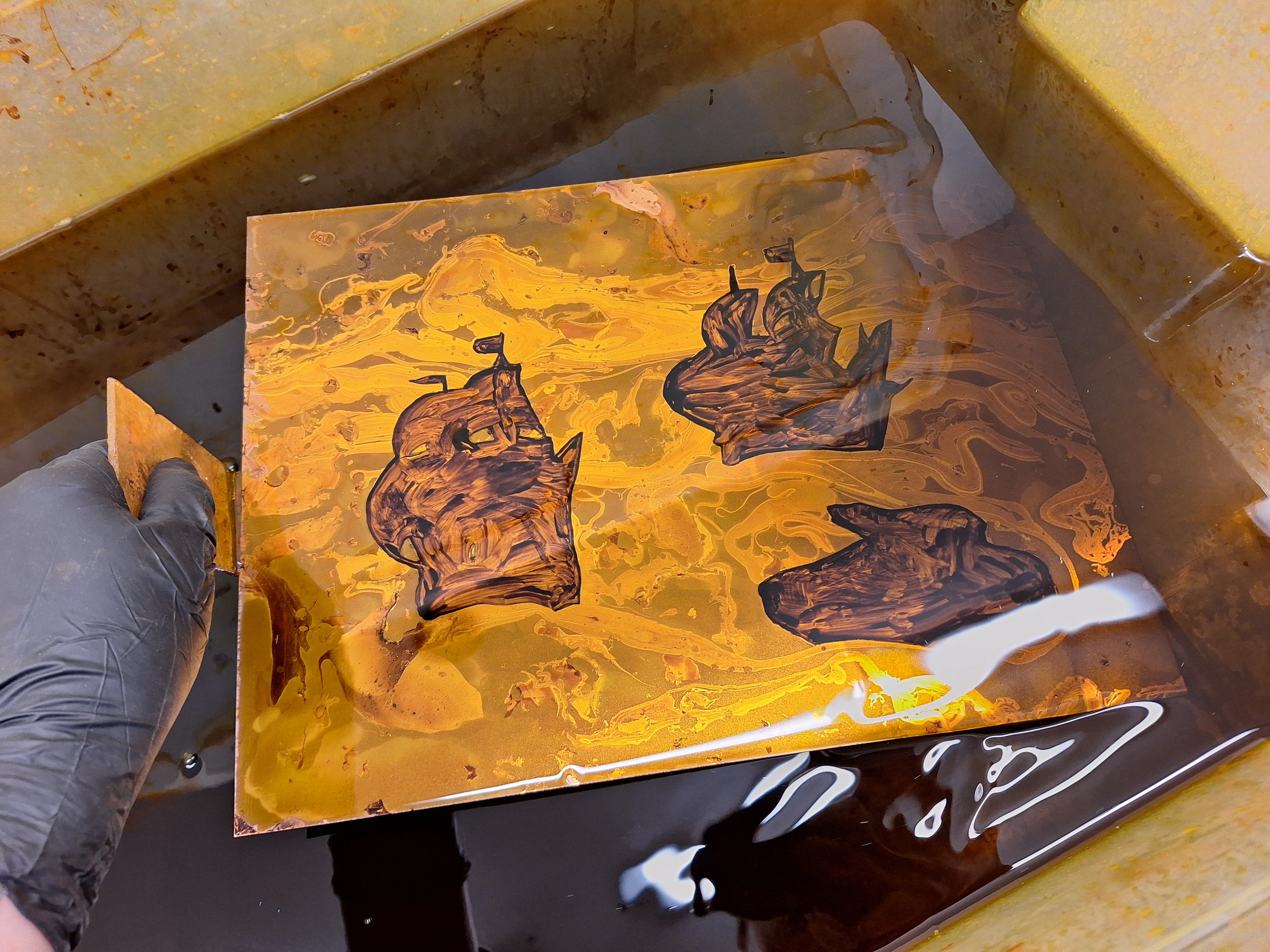

As my residency contribution, I decided that I wanted to host an introductory linocut course. I truly believe in the power of craft and collective workshops, and that the art making, maybe even more so than the art itself, makes for happier human beings and better communities. The reason why I chose to focus on linocut printmaking, is because it is a printmaking technique that does not require the use of a printing press or toxic solvents. It can be done at home using a hand-printing tool, and the inks can be cleaned up with soap and water. My aim was therefore to give the workshop participants the foundation and confidence needed to be able to master the art of linocut printmaking at home, without needing access to a professional print studio.

I wanted the course to run over two days in order to go more in-depth and take the class beyond a very elementary introduction to linocut. During the first day we learned how to make a basic single-coloured linocut print by experimenting with different tools for mark making and different methods for printing. On the second day we experimented with different ways of printing a multi-coloured print, using layering and jigsaw puzzle techniques, as well as applying colour gradients.

Photo: ARTICA

I am so impressed with how many amazing prints our wonderful participants managed to produce in the course of two half-day sessions! It was also great for me getting to meet some more of Longyearbyen’s long-term residents. It is fantastic to see what ARTICA, and the workshops and events which are hosted here, means for so many in this town. It has grown into a truly wonderful community, much thanks to the current staff, Charlotte and Lisa. That being said, with Svalbard having a higher turnover of people than other places, they stress the importance that people form an affinity and positive relation with ARTICA itself as a cultural institution and social meeting place, and not just with the individuals who work here. I truly hope my workshop helped contribute to this, and that many will continue with printmaking after this weekend.