This little dot of buildings is Longyearbyen - the world’s northernmost town sitting at 78° north. The last port of civilization before the North Pole. When you live in Svalbard, this becomes your lifeline and your world. It has (almost) all the comforts you could possibly need. A supermarket. A hairdresser. A spa. A whisky bar. A Thai take-away. A hospital which will at least take care of your most basic emergencies, such as a broken leg.

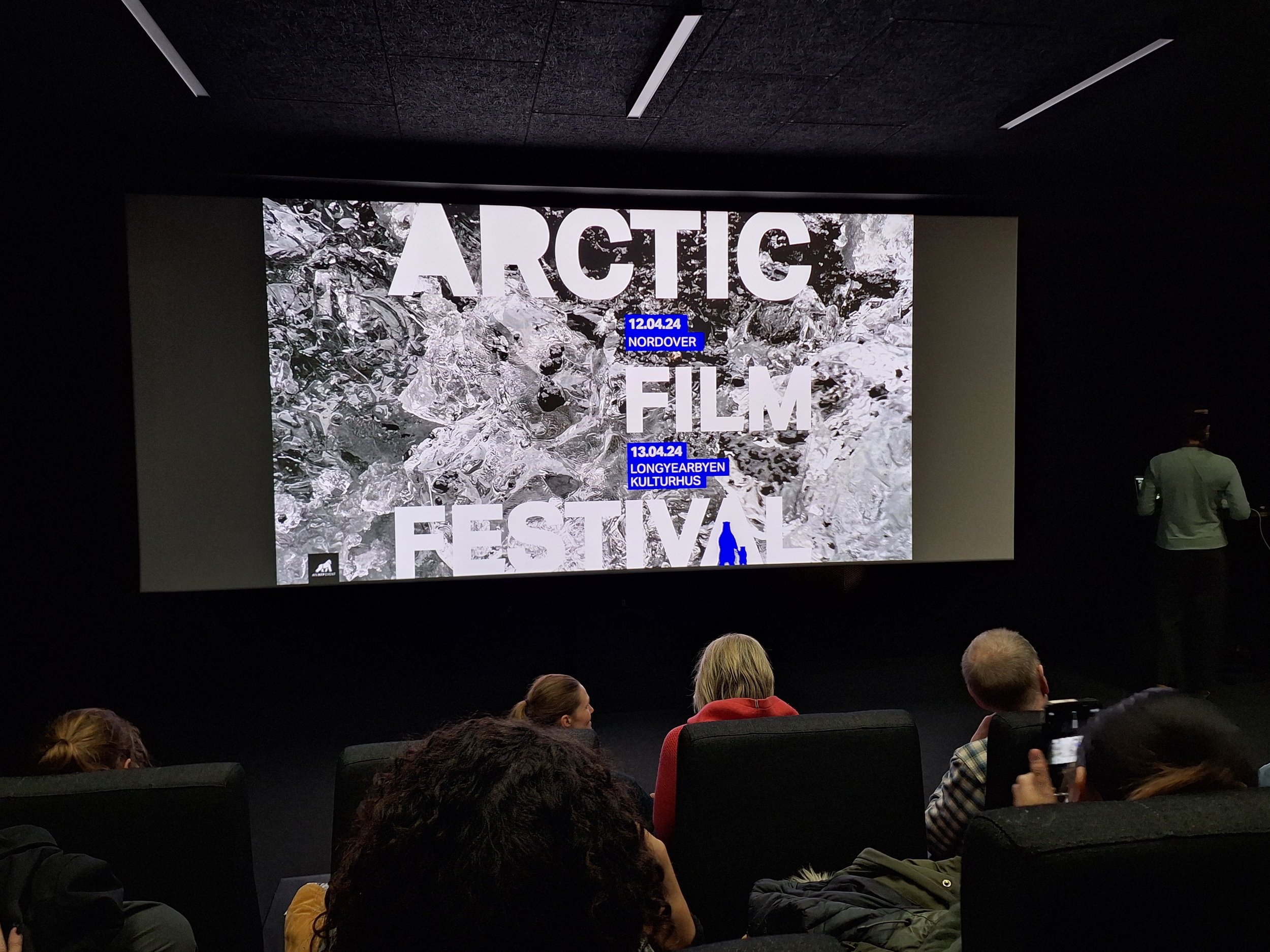

As I spend my Saturday doing research in the library and enjoying fried rice for lunch at the local Thai restaurant, I feel for a few hours that Longyearbyen has all the semblance of a normal Norwegian town - it just happens to be a very cold dot in a seemingly endless land of icy mountains. Although a community of a mere 3000 people, I can attend art exhibitions, drink fancy cocktails, listen to interesting talks at the university, go to film festivals and and attend plays.

The truth is though, that Longyearbyen is anything but normal, and once it starts getting a hold of you (which it will), you must not be deceived into thinking that it is so. In many ways, this town can be as beautiful and brutal as its surroundings.

Many people, and to some degree myself, have a romanticized and almost fetishistic view of Svalbard and the Longyearbyen community. For me, and so many others, coming here is an adventure. An escape from civilization and our busy lives at home. However, for some people, life in Longyearbyen can become somewhat of a tragedy that one either knowingly or unknowingly walks into.

The Svalbard Treaty of 1925 recognized Norway’s full sovereignty over Svalbard. All signatory nations however, were given equal rights to establish commercial activities here, mainly related to mining, fishing and hunting, and in more recent times tourism. (The treaty restricts any military uses of the archipelago). Norwegian authorities may exercise the right to regulate activities, but this must be on conditions not enforced due to nationality. (As you can imagine, the terms of the treaty is often up for discussion, with its signatories often interpreting it in very different and conflicting ways).

Due to the unique nature of the Treaty, Svalbard is the only place in the world where a person can settle down without a visa or residence permit. As long as you have the means to support yourself and a house to live in, you may stay. With the rise of travel and tourism over the past twenty years, Longyearbyen has gone from being a mainly Norwegian town to an international melting pot where almost half the inhabitants are non-Norwegian.

Svalbard is run according to its own set of rules and regulations. Taxation is lower than on the mainland, and is stipulated to only support Svalbard and in no way directly benefit the rest of Norway. Due to this however, Norwegian social security does not extend to Svalbard, and nor are there GPs, care homes or mental health services here. As a non-Norwegian national, living and working at Svalbard for decades does in no way give you the rights that a Norwegian citizen might enjoy back on the mainland. In fact, were you to apply for a Norwegian citizenship, your years at Svalbard will not be taken into consideration. Svalbard is, in many ways, a tantalizing free for all no man’s land, while simultaneously imposing on you some severe limitations.

This week I finished reading the book “Annleislandet Svalbard: små liv i storpolitikken” by Line Nagell Ylvisåker, which I would highly recommend. Reading this book has been a real eye-opener, causing me to realize how little mainlanders know of this place. In Ylvisåker’s book, we encounter some of the foreigners who have settled in Svalbard for various reasons, and learn of their stories.

One story is that of Omid, an Kurdish asylum seeker who fled from Iran and tried to gain asylum in Norway. When his application was rejected, he was told by friends he could settle in Svalbard. He arrived in 2008, the week before passport controls were introduced. However, nobody told him that he could not leave again without the necessary papers. He became a “free prisoner caught in the arctic ice”. Omid has learned Norwegian and worked at Café Fruene, Longyearbyen’s primary establishment for over a decade. He is now in his forties, with no choice but to stay in Longyearbyen or go back to Iran. In 2019, he was finally able to procure the necessary papers to visit mainland Norway as a tourist for three months. While he says Svalbard is his home now, there will come a day when he is no longer young and healthy and able to take care of himself. He, and everyone else, knows that there is little mercy to be had from Norway when that day comes.

We also follow the story of Varisa. Her parents brought her from Thailand to Svalbard when she was only three years old. At Svalbard they could earn a good living through running a cleaning company, and offer Varisa a life of material welfare she could not expect back in her birth country. She has grown up speaking both Norwegian and Thai, but never quite managing to feel quite at home in either culture. She is now about to start university, but unlike her Norwegian friends, she cannot apply for studies on the mainland without having to procure a visa. Despite growing up on Norwegian land, she is fully aware that mainland Norway will never recognize her as one of their own. Svalbard provided her parents with the opportunity for a better life, but at the same time their decision placed Varisa in a difficult situation that she herself had no control over.

Life in Longyearbyen offers art, discussion forums, films and cosy restaurants.

Having spoken to many of the locals here, they confirm the situations described in Ylvisåker’s book. Many come here with the intention of staying for just a year or two, but end up falling in love with the place. (And trust me, there are numerous reasons to fall in love with Longyearbyen). However, they know their situation will always be precarious. One woman I spoke to has a child with special needs. There was a danger of her having to take her whole family back to her home country, because her child could not receive adapted education here. Ylvisåker herself also knows that she will one day have to leave Longyearbyen. After all, this is not an establishment for the sick and the elderly. Longyearbyen has a great turnover of people. On average, people live here for 5-6 years. This means you can never really know who will stay and who will leave. Forming tight bonds can be difficult, investing time and energy into people can feel less than fruitful. Some children find it too scary to form deep connections, because they never know if and when their friends will leave. In some ways, the term “local” in relation to Svalbard is a misnomer. There are no locals. We are all just visitors - whether it is for three months or twenty years. You cannot be born here, and you cannot be buried here. This land does not belong to any of us.

With increasing geo-political tension in the arctic areas, Norway is tightening its reins over the islands. In 2021, a new law was introduced, which took away foreign residents’ right to vote in Longyearbyen’s local elections. This means that people like me can come here and vote, whereas residents such as Omid cannot. This naturally came as a great shock to the people up here, and stirred up great rage and sadness, as it further highlighted the class divides of this beautiful, but brutal town.