This week saw the last sunset for four months. From now on, the sun will be sitting higher and higher in the sky with each passing day, and falling asleep will prove increasingly difficult. To mark the occasion, we went on a late night stroll to enjoy the last beautiful plays of pastels which the setting sun throws over the snow. (The light here really is unbelievable and surreal, and impossible to capture on camera). We also walked past loads of adorable Svalbard reindeer. They are found only on Svalbard, and are the only type of reindeer native to Norway. They have adapted to harsh arctic conditions, and wander around Longyearbyen completely unfazed by people and noisy snowmobiles.

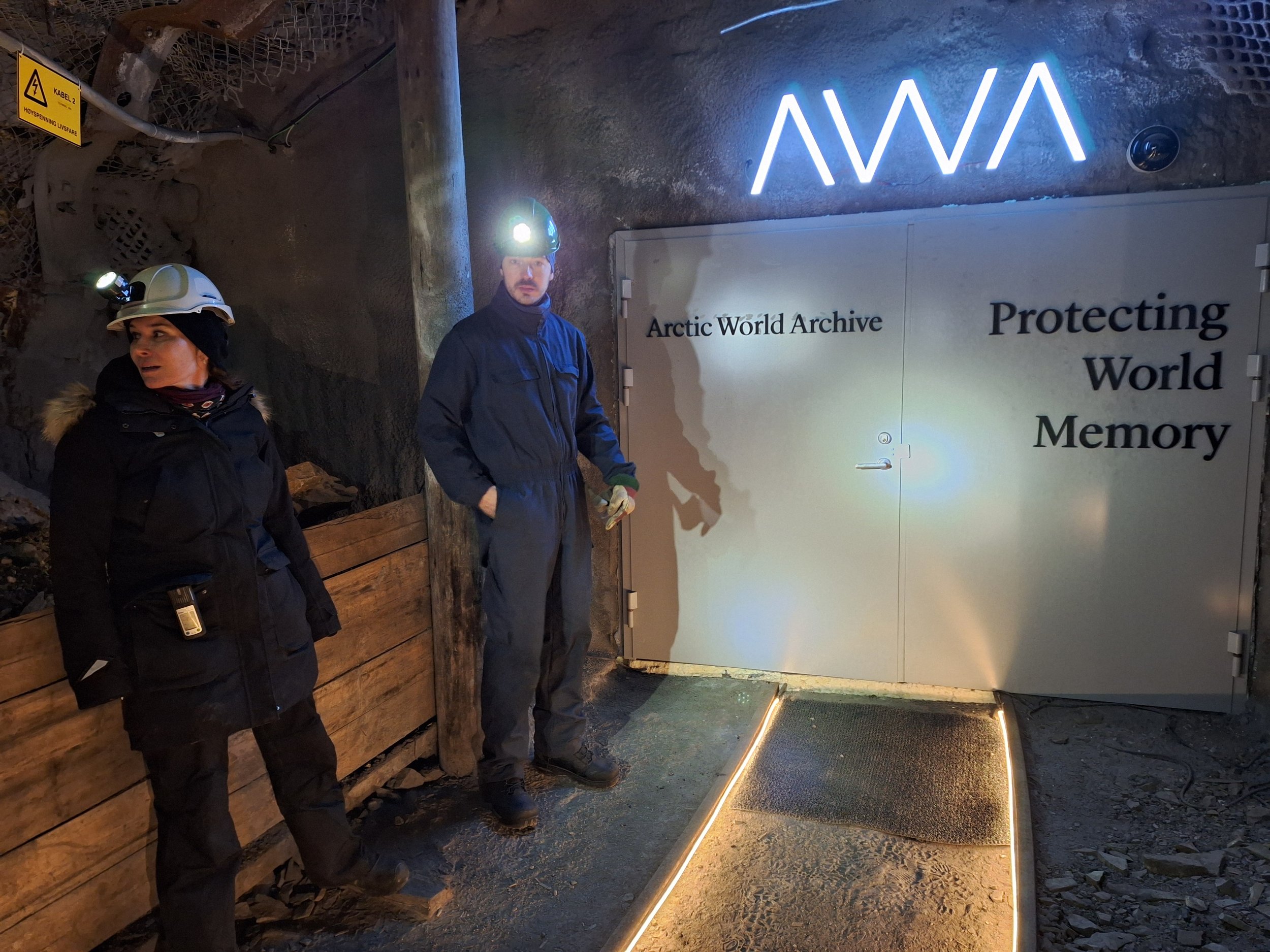

With the weather turning over the weekend, and powerful gusts of winds sweeping in over Longyearbyen, I have been enjoying my days in the studio. Although I have been going to Artica almost every day, Svalbard hits you with so many impressions that it takes a while for you to process things and translate this into artworks. I spent a lot of my first month just sightseeing and collecting information, looking for connections between prevalent themes here and the themes I have been exploring in my own art.

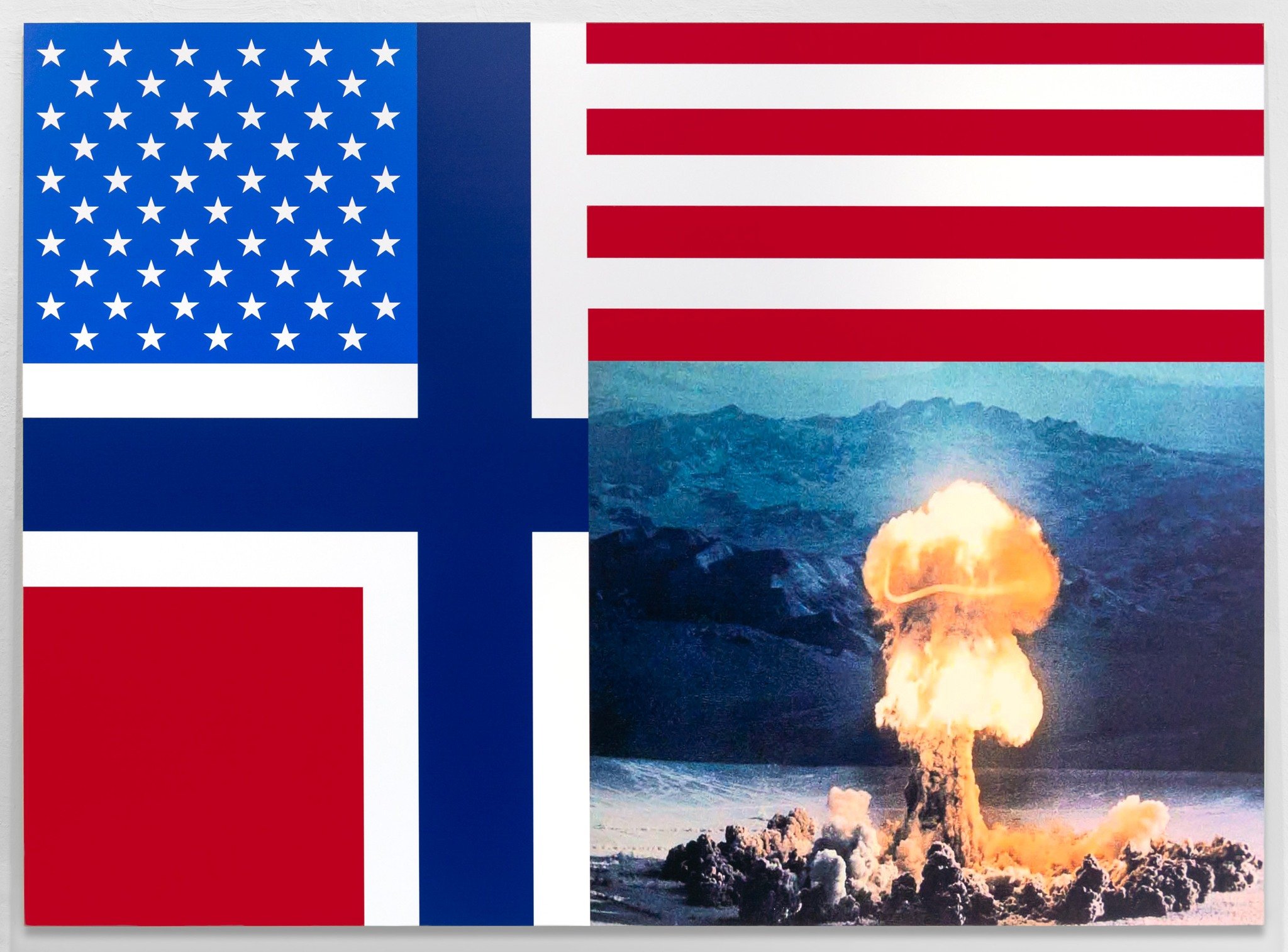

I have been mainly intrigued by the Arctic as a “stage” for exploration and geopolitics, as I very much link this to my own family history, which in many ways was formed by colonialism and geopolitical strife in and around Singapore. I see many resemblances and ironies between the European scramble for territories in South East Asia, and how we are now very protective of our resources and territories in the Arctic, as many powerful (Asian) nations are strategically placing themselves along the northeast passage as precious minerals and new sea routes are emerging with the melting ice.

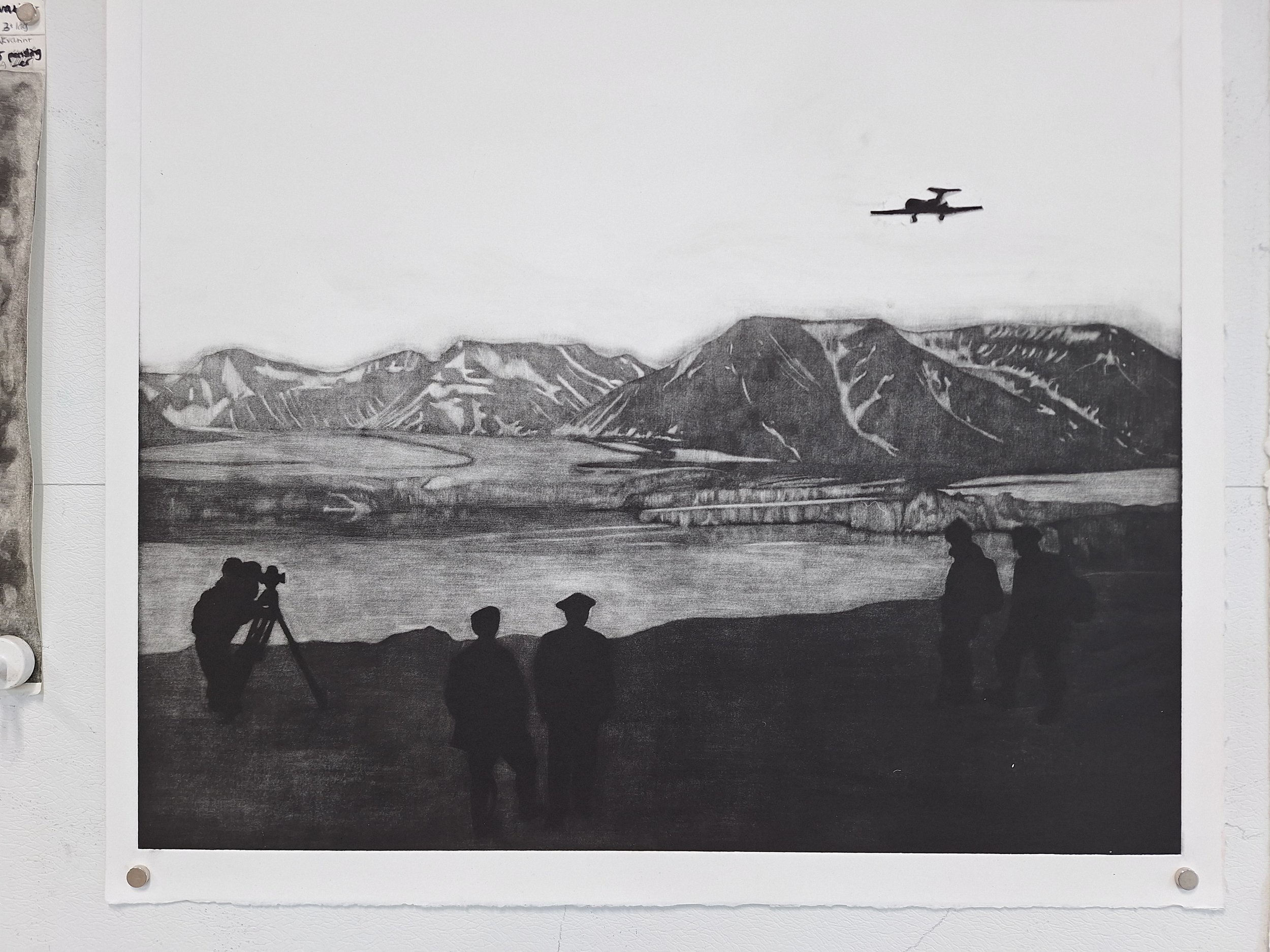

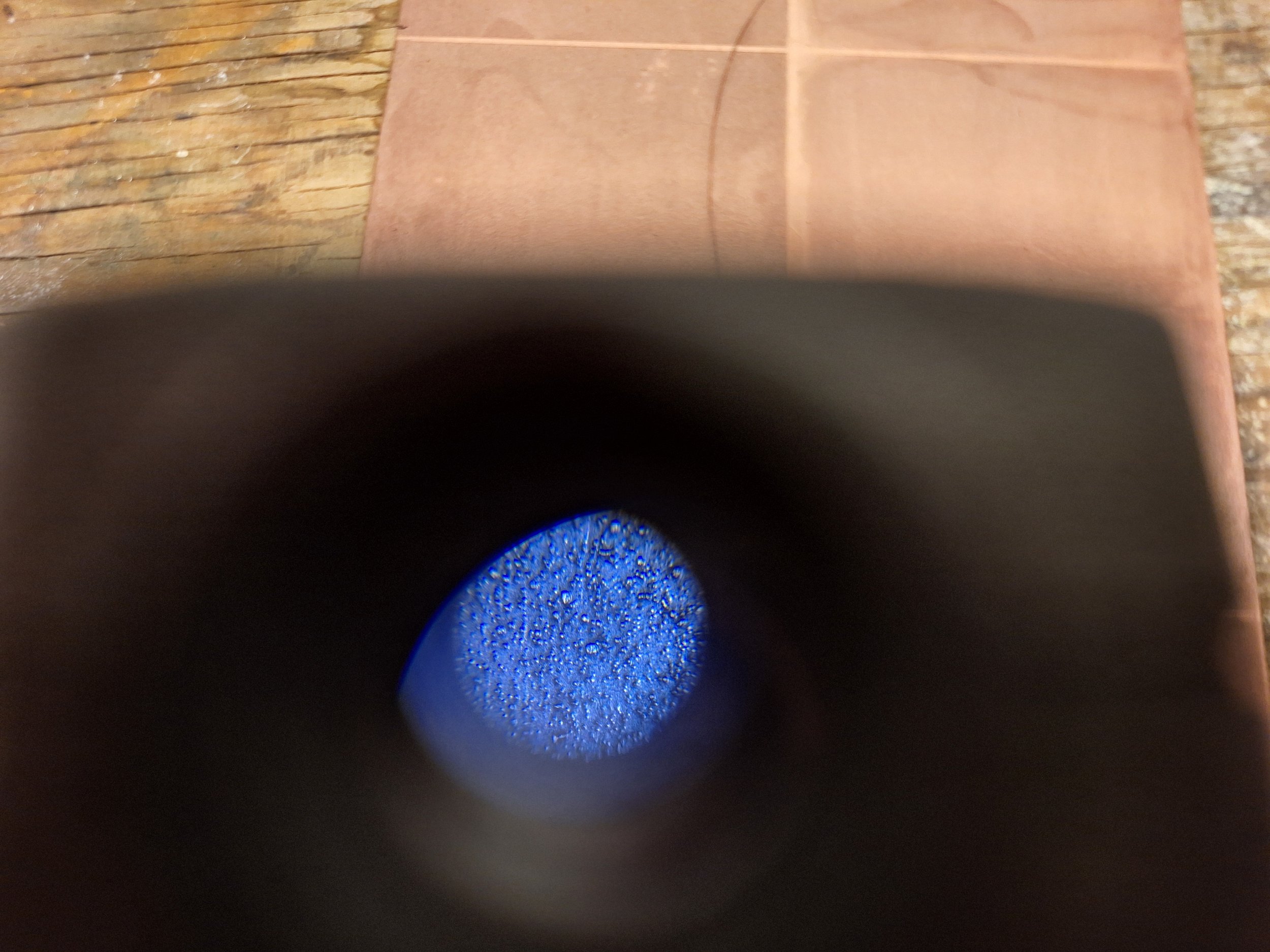

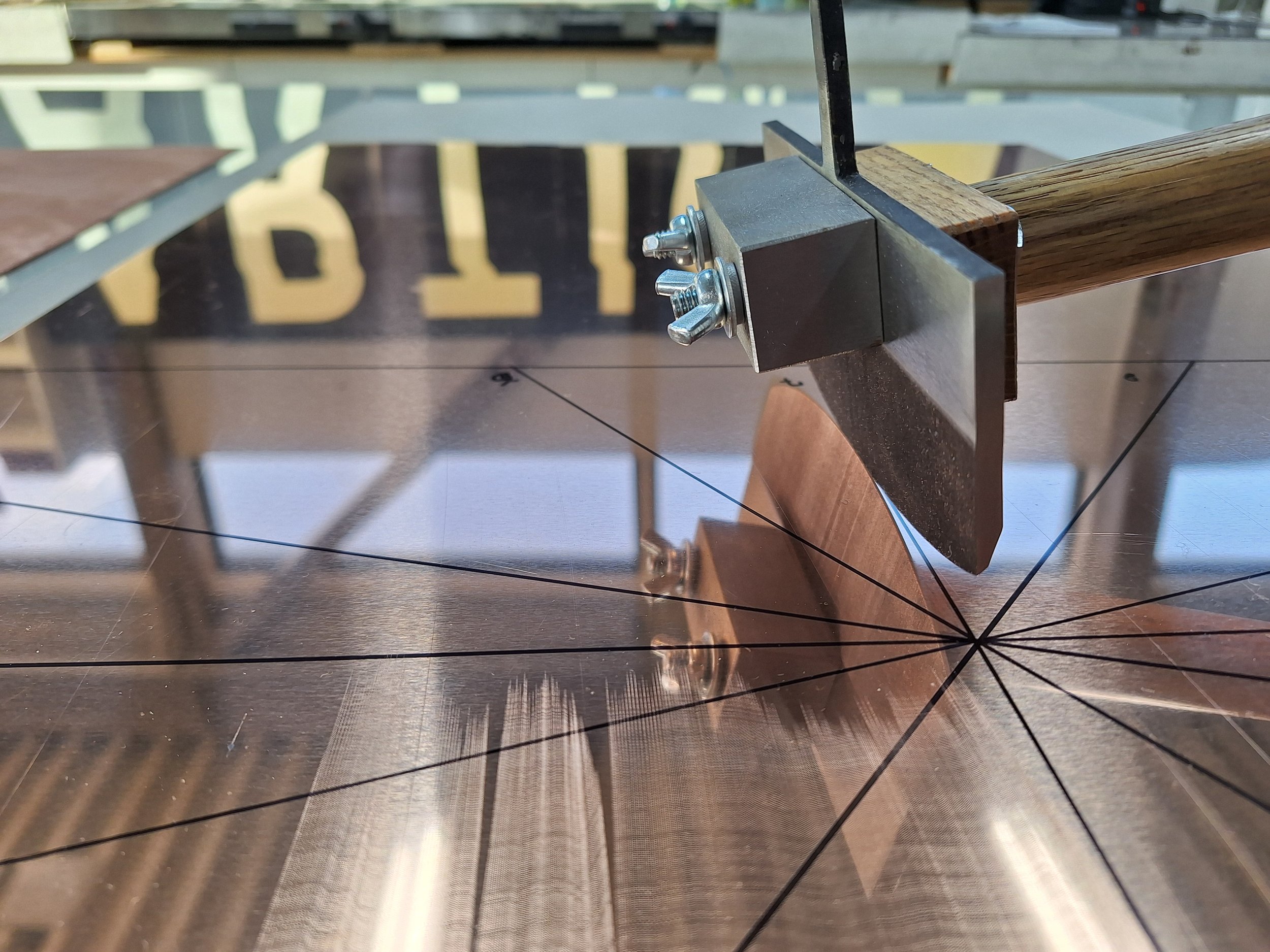

Parallel to my research, I have also worked on developing a suitable visual language. Two whole weeks was spent creating a pretty large mezzotint, which is still a work in progress. The motif is based on old photos found in the digital archives of Svalbard Museum, and features a view from the old Svea mine. In it I have juxtaposted a series of figures - two 1920s Scandinavian coalminers, a 1980s Polish geologist, two 1930s English explorers, Amundsen and Nobile’s airship “Norge” which flew from Svalbard to the North Pole in 1926, and an airplane heading into the mountains. It could be the Russian Topolev which crashed into Operafjell in 1996, with the Scandinavian coalminers here watching their Russian and Ukrainian peers perish. Or it could be a modern tourist plane, the coalminers observing how the rising tourism industry is overtaking the dominant role they once held at Svalbard. It is an open-ended story, an attempt to draw lines between past and future, and how the Arctic as a stage for self-realization and geopolitical strife is as prevalent now as it was then.

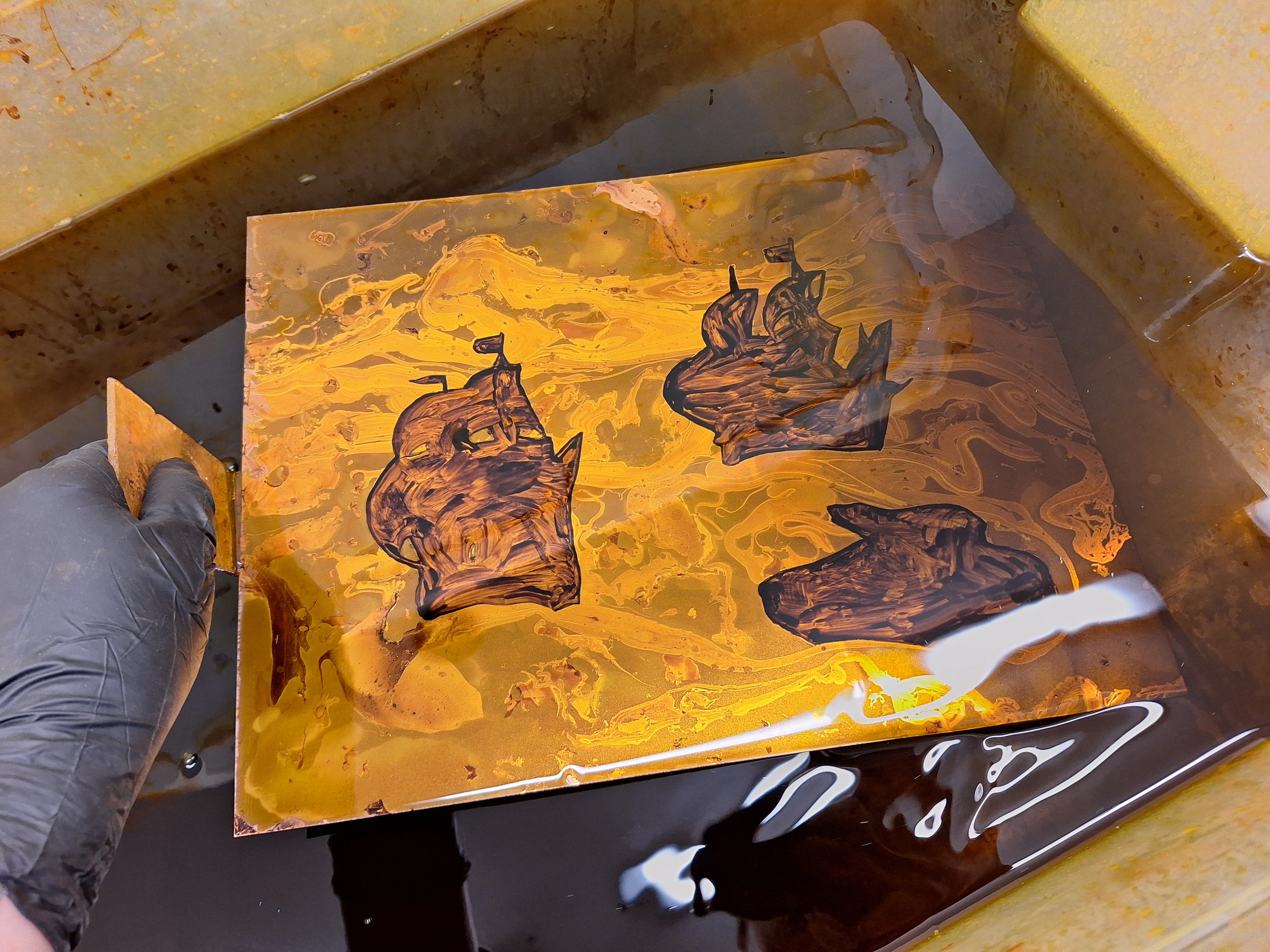

From last week’s residency dinner and presentation at Artica, where I demonstrated how I had made and printed my mezzotint plate.

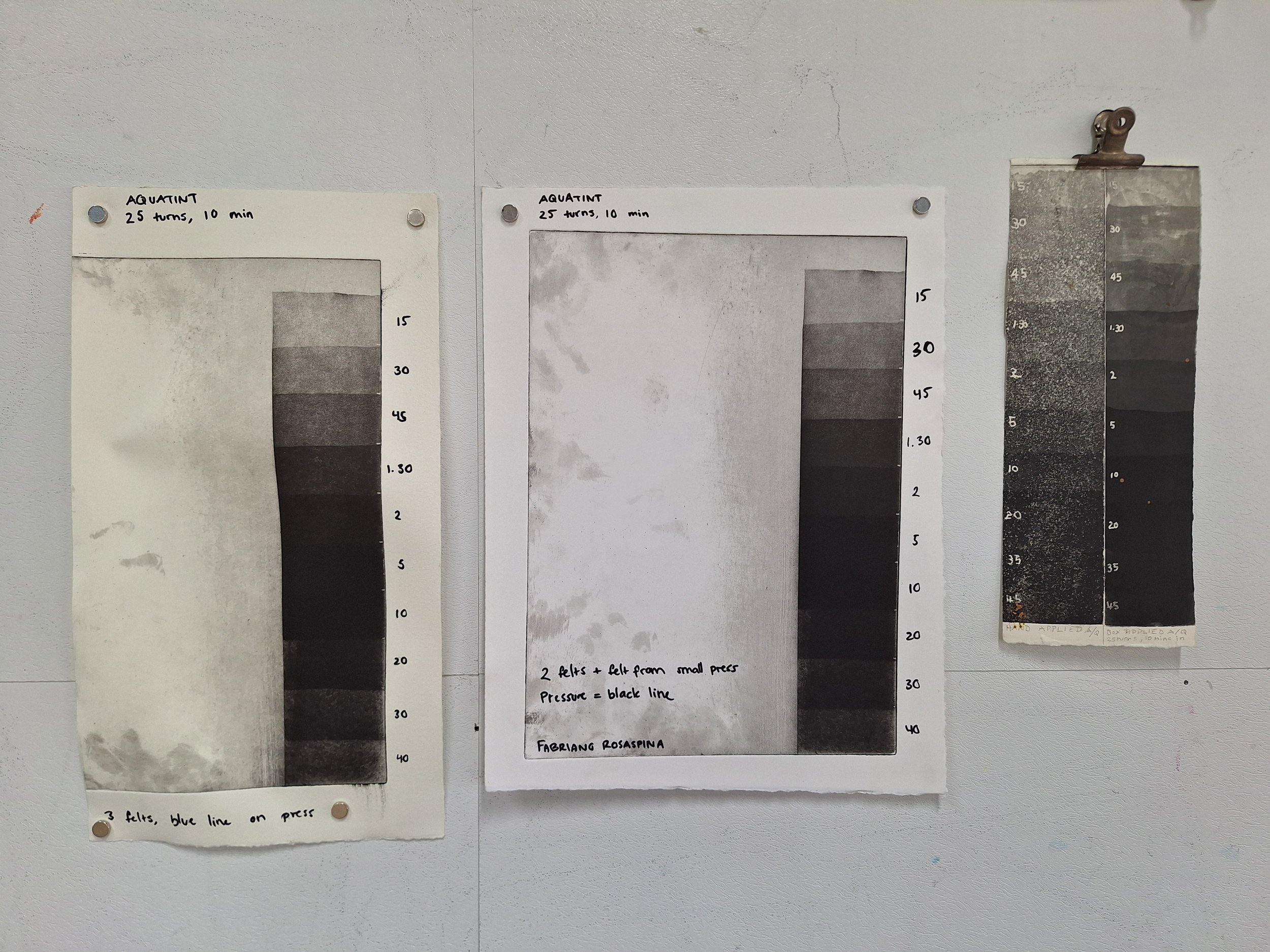

This week I decided to abandon mezzotint for a bit. While it is one of my favourite techniques, mezzotint tends to lock me into a slightly timid and naturalistic style. (It is also extremely time consuming). One of my goals before coming up here was to be a bit more bold and experimental, trying out different techniques and expressions and adopt a more playful approach to art. I also wanted to work more physically and less theoretically, letting the material and medium control the process more than a predetermined concept. I therefore decided to make some aquatint plates where I applied a hard ground marbling, letting the randomness of the marbled pattern determine the contents and composition of the image.

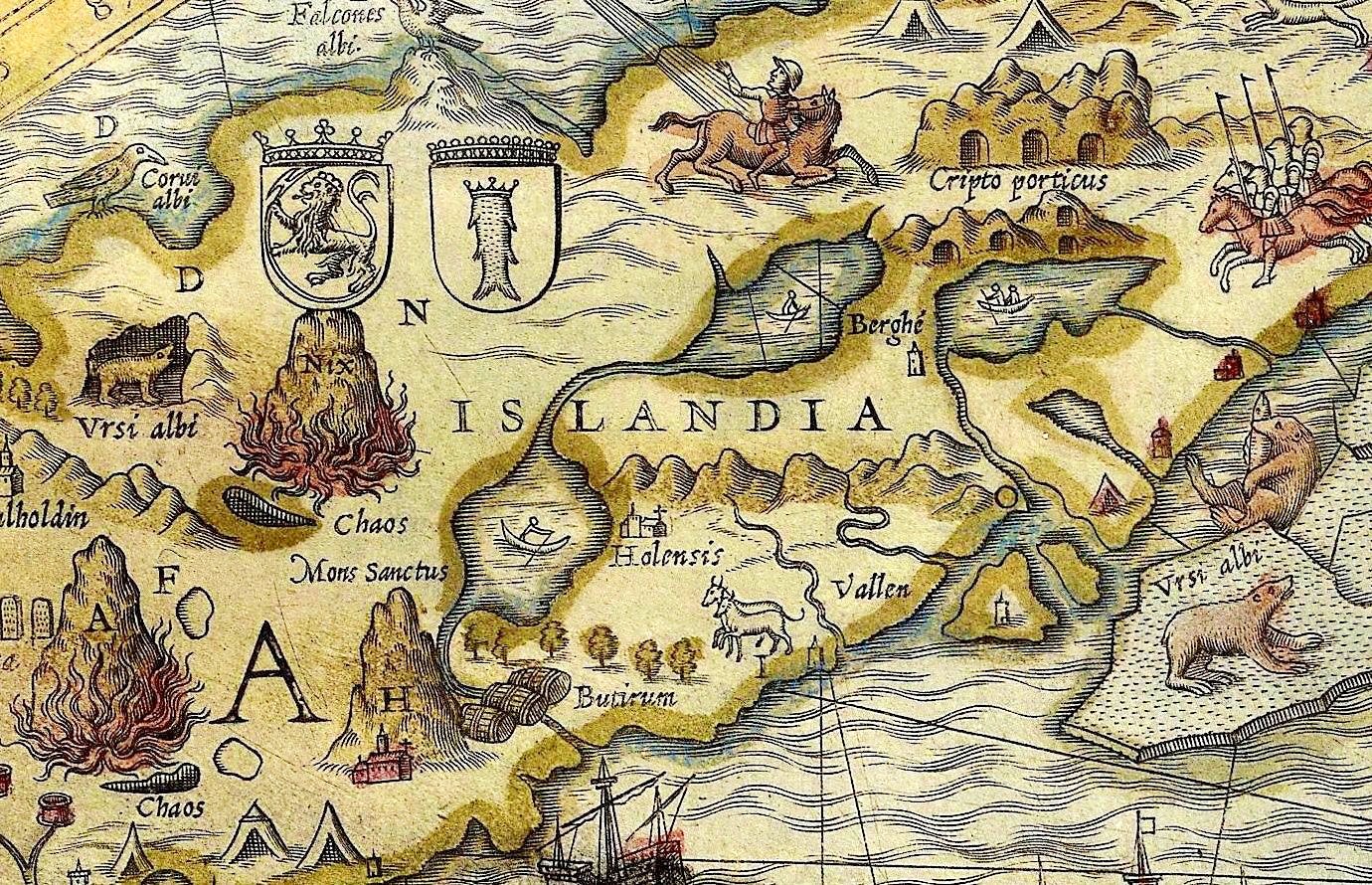

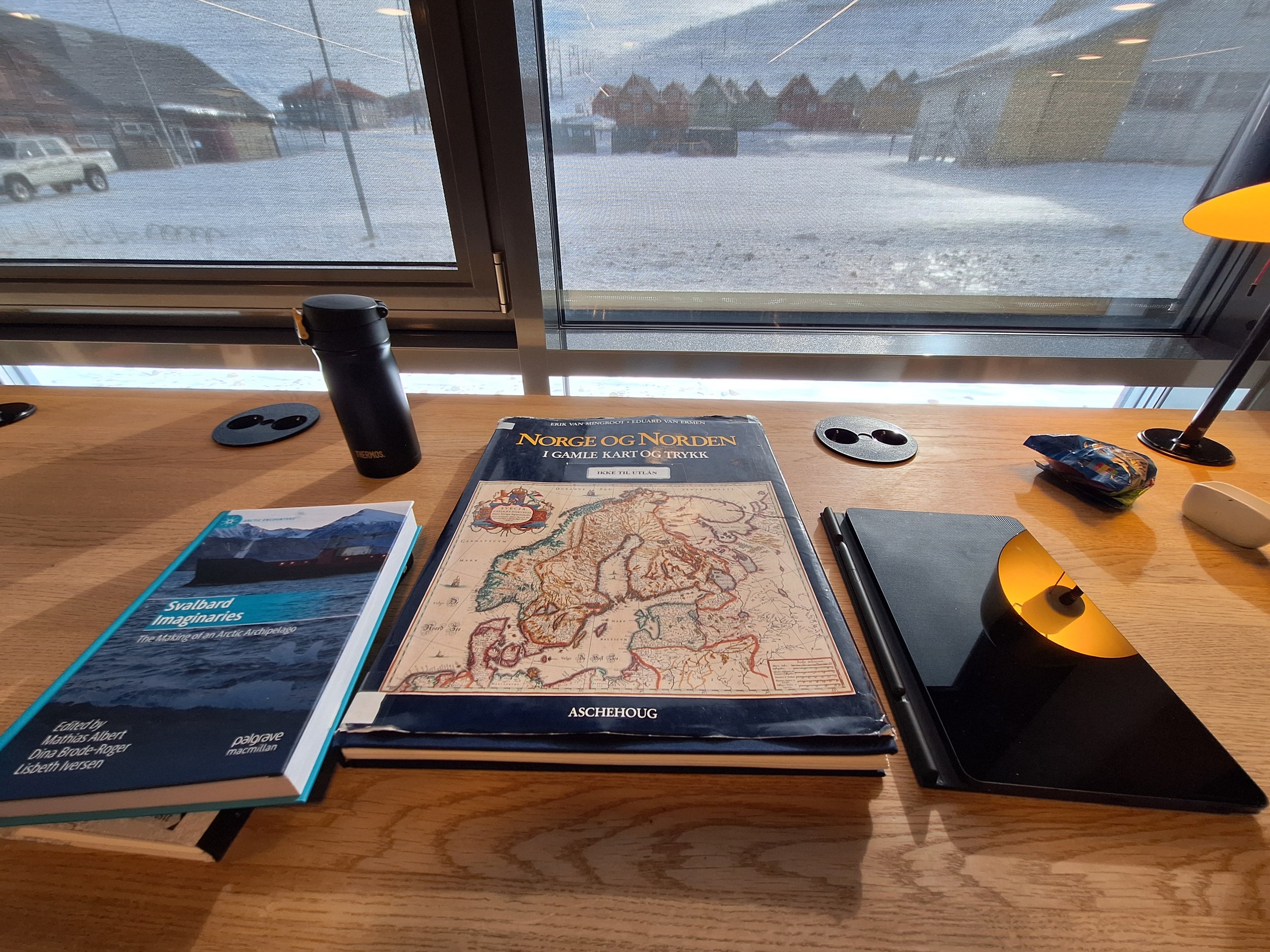

To me, the marbling was strongly reminiscent of water and oceans, and I reverted back to the research I did during my first week here when I visited Svalbard Museum and looked at various old maps of the Arctic regions. Using Pen Up on my Samsung pad, I photographed my marbled copper plates and made them part of digital collages where I added elements such as ships, polar bears and sea monsters from a variety of old northern maps. While I work with old techniques, I love the opportunities that digital tools open up to me. However, I always revert my digital sketches back to something physical, and through the printmaking process the final image takes on a life and visual quality of its own.

The ships I am using in my first composition are based off of ships from the Barentsz map. This map was created after the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz “accidentally” discovered Svalbard in 1596. The boats on the map are very small, and as I am making mine larger and more detailed, I had to study quite a few drawings of 16th century ships to get a grip of how all the numerous sailing mechanisms were connected. This is the first line etching I am doing in over a decade, and I have been enjoying the process so much!

This new project has been such a breath of fresh air to me. For a long time now I have felt the need to free myself from only working with portraits and personal family histories, as well as remove myself from the very naturalistic style which I sometimes tend to adhere to. I have been wanting to engage in a greater variety of subjects, and explore historical ways of stylizing imagery. I feel that these new images are a step towards that goal. Most importantly, the subject of sea faring, exploration and East-West relations still feels greatly personal to me. Still a bit on the fence about the final product, but that might just be because this visual style feels very new and different to me at the moment.

Colour test print of “Hic Sunt Ursi Albi” (“Here There Be Polar Bears”)