Between the 14th and 16th centuries, it became a widely established truth that the North Pole consisted of a black magnetic rock, which would account for why compasses always pointed north. Surrounding the Pole was a giant whirlpool sucking the ocean into the bowels of the earth like a funnel. Enclosing the whirlpool were four masses of land, each divided by narrow channels through which inward currents would flow.

Humanity’s idea of the North Pole was largely formed by the map Septentrionalium Terrarum by Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594). First published as part of a larger world map in 1569, a larger stand-alone map of the Arctic was published posthumously in 1595. Although it looks funny to our contemporary eyes, with the map even suggesting the presence of Pygmies just south of the North Pole, Mercator based this vision of the Arctic on the most credible accounts available to him at the time. The most influential, called Inventio Fortunata [Fortunate Discoveries] was a 14th century travelogue written by an unknown source. In Mercator’s words, it traced the travels of “an English minor friar of who traveled to Norway and then “pushed on further by magical arts.” Another source came from two explorers, Martin Frobisher and James Davis, who had travelled as far as what is now northern Canada. They described powerful currents with massive ice bergs being carried away as if weightless - which would account for the idea of the whirlpool close to the pole. There is one thing worth noting to Mercator’s credit. He was, and rightly so, convinced that the magnetic pole was separate from the geographic pole. His map therefore features an extra magnetic rock on the upper right section to account for the noticeable deviation of compasses.

Septentrionalium Terrarum by Gerardus Mercator, first printed posthumously in 1595. This is an example of a later edition published by Jodocus Hondius, which also includes Spitsbergen (now Svalbard), after it was discovered in 1597.

The suggestion that there must be a large mountain of lodestone at the North Pole to account for the earth’s magnetism goes back to at least the 13th century, not long after the invention of the compass. The vision of the North Pole as a black rock surrounded by four landmasses is also present in Johannes Ruysch’s canonical shaped world map, published as early as 1507-8.

Universalior Cogniti Orbis Tabula, Ex recentibus confecta observationibus [A more universal map of the known world, constructed by means of recent observations] by Johannes Ruysch, published 1507-1508.

In the Age of Exploration, which saw increasing trade with the East, the Western world hoped that through the open channels surrounding the North Pole, they could reach the other side of the globe in a fraction of the time that it took to sail around Cape of Good Hope in order to reach the ports of India and China. The immense forces and crushing powers of the arctic drift ice soon proved this to be impossible however, and many a fatal expedition stood testimony to this. By the mid 1600s, the view of the North Pole as an economical and time saving maritime highway to the East had become obsolete - explorers who had just barely made it home reporting that the polar region seemed to consist of nothing but inhospitable, impenetrable ice. The Arctic thus became “the Silk Road that never was”.

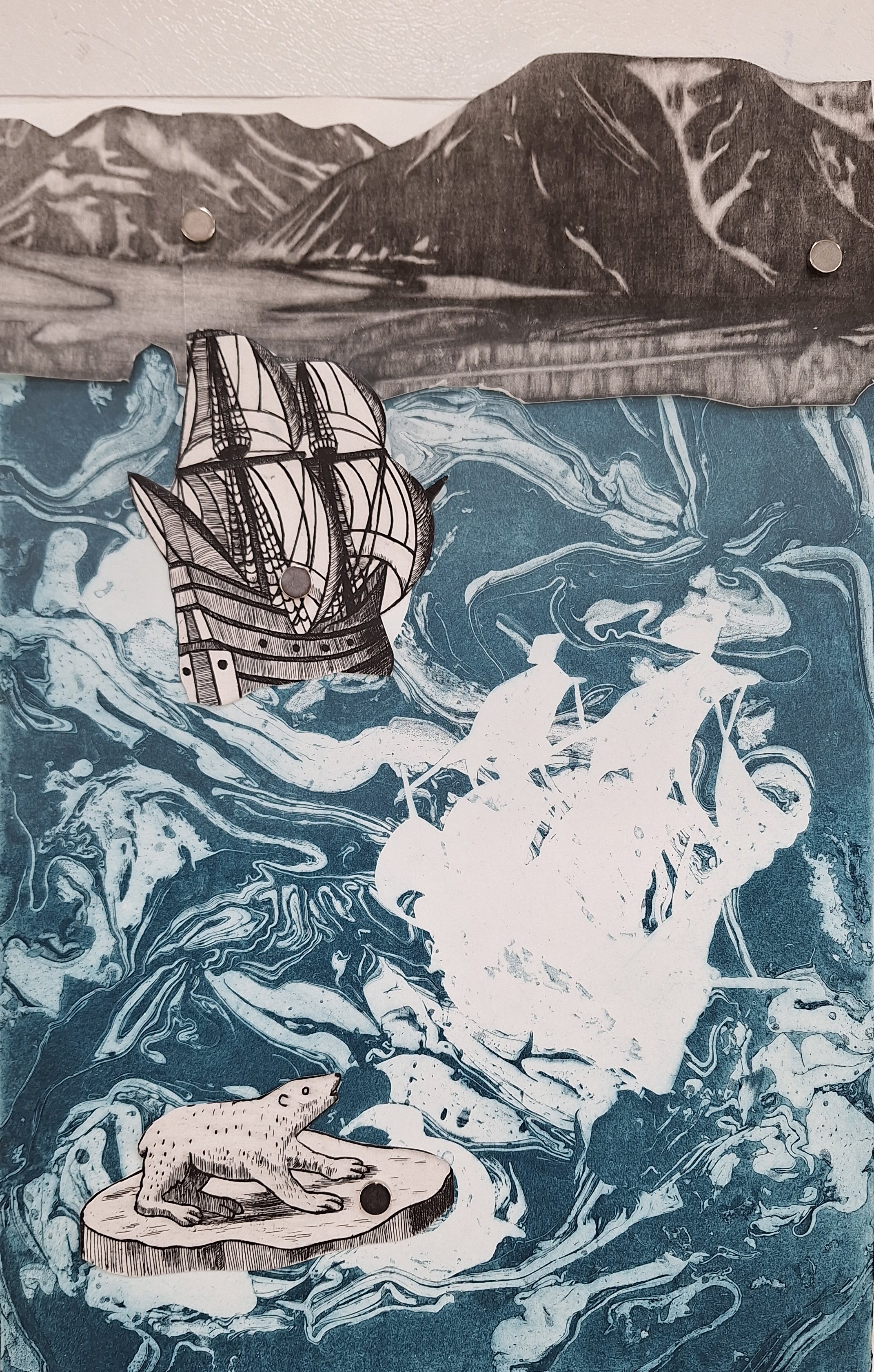

The illustrations below depict the perils that the crew of Willem Barentsz’ third and final expedition had to face in their attempt to discover a northern sea route to Asia:

While long discarded as an unrealistic dream, climate change and rapidly melting polar ice is turning what was once a Renaissance utopia of profitable sailing routes into a very imminent contemporary reality. The Ship Yard Blog has a very interesting article on this, describing how in 2017, the Russian tanker Christophe de Margerie made the first journey from Norway to South Korea without being escorted by an icebreaker. Not only did this fuel hopes of establishing a direct maritime link between the giant Yamal gas field in Russia and the markets in East Asia. The Arctic might, according to experts, also hold 22% of the world’s undiscovered hydrocarbons which may soon be up for grabs.

With these developments, a whole set of geopolitical questions in the north are arising - something which we Norwegians are noticing both in northern mainland Norway and on Svalbard. Together with Russia, Canada, Denmark and the United States, Norway has submitted claims for the right to explore the continental shelf of the Arctic Ocean. In addition to this, China has defined itself as a "near-Arctic state" for the past decade, and thus plans to play a growing role in the region.

For the past couple of weeks, there have been lots of talks and debates regarding the sale of a large property on Svalbard near the Recherche Fjord. Currently on sale for over 300 million Euro, the land measures 60 square kilometres (roughly the size of Manhattan) and boasts mountains, glaciers and a five kilometre coastline. It is, by all accounts, the last privately owned land in Svalbard, and the last private land in the world’s High Arctic. In the sales prospect, it has been promoted as a property of unprecedented geopolitical and strategic importance. The owners, Kuldspids AS, welcome all bidders - individuals, companies and governments alike - from countries who have signed the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, and are thus entitled to exploit the region’s natural resources on a similar level to Norway. One of the signatories, Russia, has for several decades maintained a coal mining community on Svalbard, via the state-run company Trust Arktikugol. The Chinese are now, naturally, sought out as highly potential and interested buyers.

Private land for sale Sore Fagerfjord, near the Recherche Fjord. Photo credit: CC/Gary Bembridge

Keen to protect its sovereignty and control over Svalbard, Norway is becoming increasingly concerned by the prospect of a Chinese sale, fearing that it might prove yet another a security risk in addition to that of the looming Russian presence. Norway's Attorney General has ordered the owners to call off the planned sale, and government ministers are proclaiming that the land cannot be sold without the approval of Norwegian authorities due to old clauses dating back to 1919. Per Kyllingstad, the attorney representing the sellers, claims that these clauses have expired. There is also a lot of discussion as to how valuable an investment the land actually is. The Norwegian government has enforced strict environmental laws on Svalbard, making any practical use of the area near impossible. The land might therefore be of minimal value, besides a symbol of prestige. However, many countries might also regard this land as a long term investment, as there is no knowing what the political landscape of Svalbard will look like in 50-100 years.

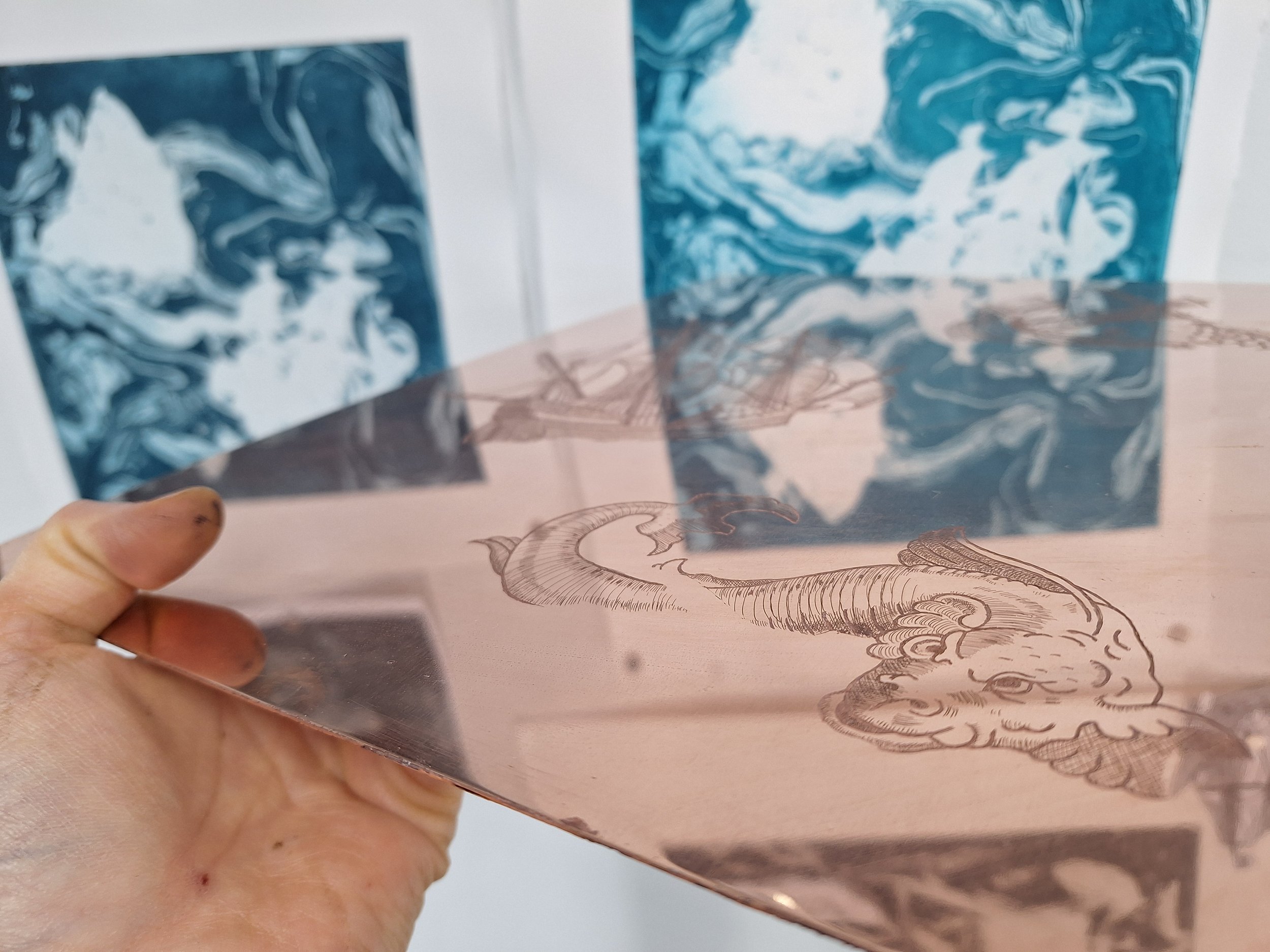

Inspired by the current news articles and debates, I have created my own map of the North Pole to reflect how centuries of technological advancement and human desires are now unfolding on a whole new scale due to climate change in the Arctic. Basing my vision of the North Pole on Mercator’s map, and juxtaposing illustrations from a variety of antique polar maps together with my own contemporary drawings of modern ships and machinery, I liken the scramble of the Arctic to a never-ending game of chess or Snake and Ladders, where we are placing ourselves as strategic pawn pieces on a global game board, where some succumb and others thrive.